Dynamic Value Relocation Table (DVRT) details

For the story that led us down the rabbit hole and straight to this post (not really, we took some detours), see How Meltdown and Spectre haunt Anti-Cheat.

Retpoline

Retpoline changes are done ad-hoc when loading a kernel module to the memory in order to mitigate Spectre CPU vulnerabilities. Retpolines allow to replace an indirect call or jump with a sequence that has a safe speculation behavior. The question is how does the OS accomplish these changes – how does it know where the replacements need to be applied? Where is all the information kept?

DVRT

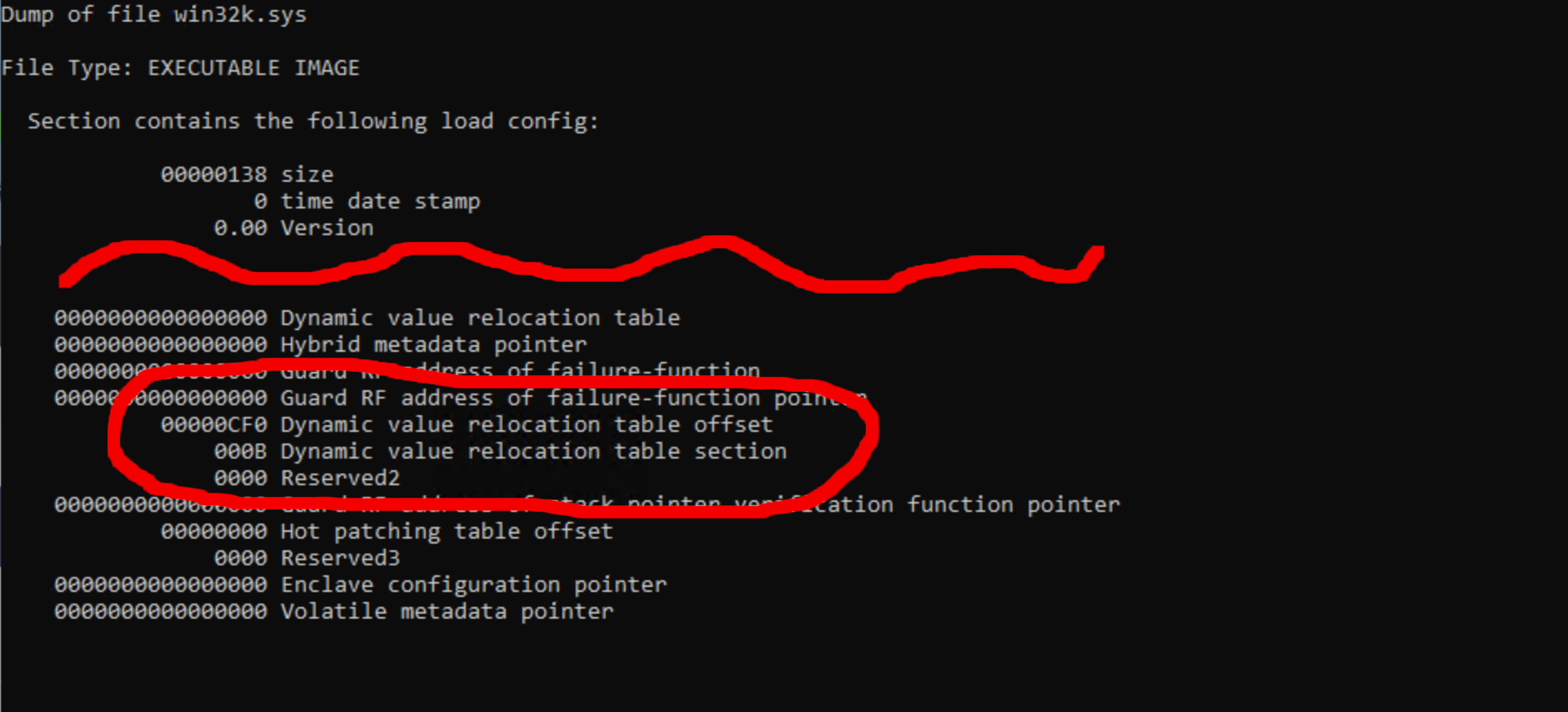

Dynamic Value Relocation Table (DVRT) is a metadata built into the binary during compilation phase. It’s not a new format designed specifically for retpoline – it was introduced in the past, but the DVRT format was extended for the purpose of mitigating Spectre v2. It can be found via the Windows PE32 load config directory of an executable file (not covered by documentation yet). For example, dumpbin /loadconfig win32k.sys will give the output below:

Note: dumpbin ships as part of the native tools of Visual Studio, use the “x64 Native Tools Command Prompt”. win32k.sys is in C:\Windows\System32.

DVRT format contains a lot of information, but for the sake of this article we will focus on just two fields:

uint32_t dynamicValueRelocTableOffset;

uint16_t dynamicValueRelocTableSection;

During the build, the compiler keeps all the metadata about indirect jumps/calls and stores them under

the .reloc section, repurposed for DVRT. At runtime, the kernel is parsing the DVRT data and applies

the retpoline patches for each reference kept there.

The retpoline can be enabled on OS level, using registry key System\CurrentControlSet\Control\

Session Manager\Memory Management\FeatureSettings. The flags responsible for retpoline are:

0x100 - FEATURE_SETTINGS_DISABLE_RETPOLINE

0x200 - FEATURE_SETTINGS_FORCE_ENABLE_RETPOLINE

The code of the retpoline sequences is stored in the RETPOL section of the kernel image. It is then

mapped to the page right after the end of the kernel module image (which means that this page is the

same for each image in the memory). All the replacements of the indirect calls and jumps will instead

refer to that page with retpolines – which will execute the control flow in the way that is safe from

speculative execution attacks.

Format

DVRT starts with the header:

struct ImageDynamicRelocationTable

{

uint32_t version;

uint32_t size;

};

Until now, there is only one version of the DVRT header (1). Size is of course number of bytes after the header that contains retpoline information. Then there are entries for each type of the retpoline (described further). Each block starts with the header:

struct ImageDynamicRelocation

{

uint64_t symbol;

uint32_t baseRelocSize;

};

Symbol field identifies one of the existing types of dynamic relocations so far (values 3, 4 and 5). Then, for each page, there is a block that starts with a relocation entry:

struct PEBaseRelocation

{

uint32_t virtualAddress;

uint32_t sizeOfBlock;

};

where virtualAddress is an address of the page for which the relocations need to be done, and

sizeOfBlock is size of all the entries for that page (in bytes).

After that there are entries for all of the places which need to be overwritten by the retpoline jump. The

structure used for those entries depends on the type (symbol) that was used above. There are three types

of retpoline so far. Entry for each of them will contain pageRelativeOffset. The kernel uses that entry to

apply the proper replacement under virtualAddress + pageRelativeOffset address. The rest of the

entry differs between the types of retpoline. Each of them is described below.

Type 5 retpoline:

Structure:

union ImageSwitchtableBranchDynamicRelocation

{

struct Parts

{

uint16_t pageRelativeOffset : 12;

uint16_t registerNumber : 4;

};

Parts asParts;

uint16_t asNumber;

};

This type is used for the indirect jumps for which the argument is put in one of the registers. The format of the instructions for which this type applies is one of:

ff(e0-e7) jmp rax, rbx, rcx, rdx, rsi, rdi, rbp, rsp

41ff(e0-e7) jmp r8, r9, r10, r11, r12, r13, r14, r15

depending on the number of the register. After applying the retpoline, the modified code will look like this:

e9(xxxxxxxx) jmp <address of the retpoline page + 0xA0 + 0x20 * registerNumber>

Address (calculated on runtime while loading the image) will refer to the retpoline for that case. At the retpoline page (which is the next page after the image ends), under the offset 0xA0 there is a 0x20 entry for each of the registers – with the proper retpoline code.

Type 4 retpoline:

Structure:

union ImageIndirControlTransferDynamicRelocation

{

struct Parts

{

uint16_t pageRelativeOffset : 12;

uint16_t isCall : 1;

uint16_t rexWPrefix : 1;

uint16_t cfgCheck : 1;

uint16_t reserved : 1;

};

Parts asParts;

uint16_t asNumber;

};

PageRelativeOffset has the same role as above. Apart from that, additional parameters used:

isCall- differentiate between call and jump instruction,cfgCheck- this value will be1if the call/jump is to the config check (which will be in a format of the call to the pointer) or indirect call to value fromraxregister. This matters when choosing which retpoline to use for such cases - offset in retpoline page will be0x2A0forcfgCheck == 1and0x2E0forcfgCheck == 0,rexWPrefix- we never encountered this flag to be set yet, so this is a field for the next blog entry :)

For example, for case with cfgCheck == 1 and isCall == 1 original code

ff15xxxxxxxx call qword ptr ds:[<cfgCheckAddressPtr>]

will be replaced by

e8xxxxxxxx call <address of the retpoline_page + 0x2A0>

90 nop

Similarly for case with with cfgCheck == 0 and isCall == 0 original code

ffe0 jmp rax

will be replaced with

e9xxxxxxxx jmp <address of the retpoline_page + 0x2E0>

90 nop

Type 3 retpoline:

Structure:

union ImageImportControlTransferDynamicRelocation

{

struct Parts

{

uint32_t pageRelativeOffset : 12;

uint32_t isCall : 1;

uint32_t iatIndex : 19;

};

Parts asParts;

uint32_t asNumber;

};

This type is dedicated to the calls or jumps to the imported functions. Original code

48ff15xxxxxxxx call qword ptr ds:[<imported function address ptr>]

0f1f440000 nop dword ptr ds:[rax+rax*1], eax

will be replaced by

4c8b15xxxxxxxx mov r10, qword ptr ds:[<imported function address ptr>]

e8xxxxxxxx call <address of the retpoline page + 0x420>

Since code of retpoline is unchangeable, the imported function address will be first moved to r10, from

which the indirect call will be performed in the retpoline code. The exact retpoline address offset in this

case is 0x420.

Similarly, for the jump instruction, the original code

48ff25xxxxxxxx jmp qword ptr ds:[<imported function address ptr>]

cccccccccc int3

will be replaced by

4c8b15xxxxxxxx mov r10, qword ptr ds:[<imported function address ptr>]

e9xxxxxxxx jmp <address of the retpoline page + 0x420>

In some cases, when import optimization feature is enabled, instead of jumping to the retpoline, the instruction can be replaced by jump directly to the imported function module. Import optimization (or import linking) is another feature that can address the Spectre v2 problem without using retpoline when certain conditions are met. It is also controllable under the registry flag

0x2000000 - FEATURE_SETTINGS_DISABLE_IMPORT_LINKING

For the cases similar to retpoline type 3, the indirect branch targeting imported function may be replaced by calling the target directly. For this to happen, the following conditions need to be met: the address has to be relatively close (less than 2 GB), the feature is on and the content of the IAT (import access table) will not change after the image is loaded. This feature is used along with retpoline and can give a significant boost to OS performance.

Conclusion

Anti-Cheat software has to discriminate between benign and illicit modifications of the game’s code.

The operating system has always made some benign changes to apply base relocation, and to store

import function addresses in the import address table. With the advent of side-channel mitigations, the

Windows kernel now patches more places to redirect calls and jumps to a retpoline section to mitigate

Spectre v2. DVRT is the structure stored in the .reloc section that describes these patch locations.

We have dissected and documented these novel data structures.

Related work: